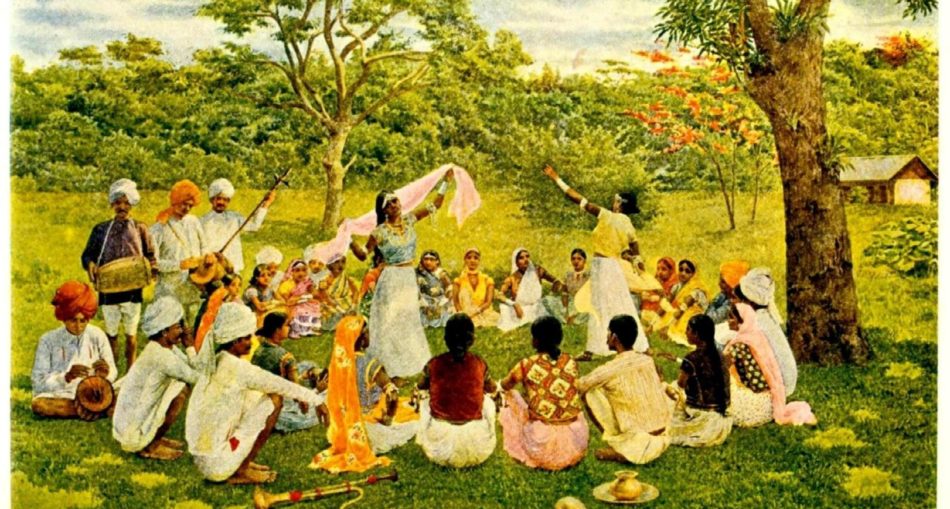

The East Indians who came to Guyana did not get to bring a lot physically but yet they made a significant impact on the country. How? They brought something that couldn’t have been taken away from them – their culture, their way of dress, the music they adore and their decorum. Interestingly, all of this has been passed down from generation to generation and up until today the East Indians in Guyana take pleasure in this customary way of life.

The East Indians who came to Guyana did not get to bring a lot physically but yet they made a significant impact on the country. How? They brought something that couldn’t have been taken away from them – their culture, their way of dress, the music they adore and their decorum. Interestingly, all of this has been passed down from generation to generation and up until today the East Indians in Guyana take pleasure in this customary way of life.

The Work of The ‘Gladstone Coolies’

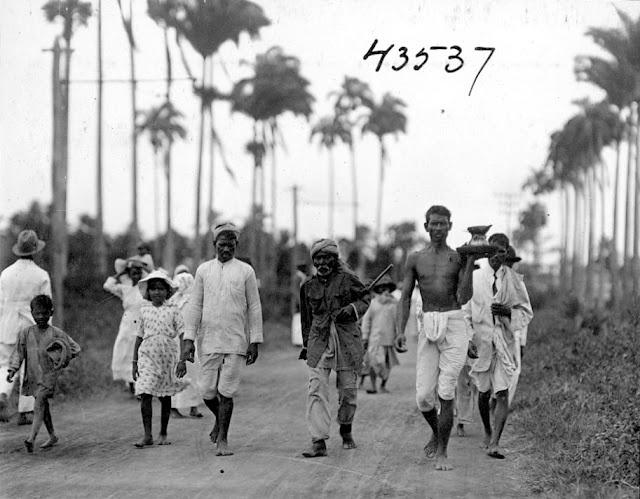

Indentured Labourers | Image Source: https://www.newsgram.com/

On May 5th 1838, the very year of final slave emancipation (Abolition of Slavery) in the British West Indies, a small batch of 396 Indian immigrants popularly known as the ‘Gladstone Coolies’ landed at Highbury, Berbice in British Guiana (Guyana) from Calcutta, India aboard the Whitby and Hesperus. This was the beginning of the indenture system which was abolished in 1917, by which time a total of some 240,000 indentured servants from India came to Guyana under a system whose essential features were very reminiscent of slavery.

The Gladstone Experiment

According to an article by Basdeo Mangru, published in the Stabroek News, May 4th, 2013:

On January 4, 1836 Gladstone, an absentee proprietor and father of England’s future Prime Minister, William Ewart Gladstone, wrote a letter to Gillanders, Arbuthnot and Company, a Calcutta firm recruiting and exporting laborers to Mauritius in the Indian Ocean. He asked for 100 able-bodied Indians on contracts for between 5 and 7 years. Gladstone’s letter detailing the attractive features of plantation life highly exaggerated the truth. The letter promised light work, comfortable dwellings, abundance of food, legal protection, free education, free medical attendance and religious freedom. The letter skilfully omitted the penalties for non-completion of work or for other infringements of the immigration ordinances.

The firm envisaged no difficulty in procuring such labourers, “the natives being perfectly ignorant of the place they agree to go to, or the length of the voyage they are undertaking.” This reply paved the way for the fraud and deceit which permeated the recruiting system. According to John Scoble, the vigilant secretary of the Anti–Slavery Society, it permitted “every scoundrel in India to kidnap and inveigle into contracts for five years, in a distant part of the world, the ignorant and inoffensive Hindoo!” The stage was now set for Indian indentured workers to labour under conditions bordering on slavery.

Of 414 Indian immigrants conveyed by the Whitby and the Hesperus (owned by Gladstone) 18 died in transit, leaving 396 survivors, including 22 women. Nearly one-half of this first batch, the ‘Gladstone Experiment,’ comprised ‘Hill Coolies’ (Dhangars, Mundas, Oraons, Santals, Kols,—generally referred to as ‘Junglies’) from the Chota Nagpur plateau, about 300 miles from Calcutta. Considered docile, simple, happy contented and hardworking, they lived an isolated life protected by dense forests which made transportation and communication difficult. In 1765 when Bihar, of which Chota Nagpur was a part, came under British rule, speculators moved into the region, purchased estates, rackrented the peasants and forced them to seek employment in the plains. Unscrupulous recruiters exploited their plight and recruited many for the sugar colonies.

On May 5, 1838 the Whitby landed in Berbice and the Hesperus in Demerara. Within a week of their arrival, Indians were dispatched to their respective plantations – Vreed-en-Hoop and Vried-en-Stein (owned by Gladstone) and Belle Vue (Andrew Colville) in West Demerara, Anna Regina in Essequibo, and Highbury and Waterloo (Davidson, Barkly and Company) in Berbice. Except on Gladstone’s estates, Indians were lodged in barrack-like structures (called logies) which measured about 100 feet in length and 20 to 25 feet in width. In Berbice the structures were smaller.

Unlike the slaves, Indians were assigned to plantation work without a ‘seasoning’ or acclimatization period. The contract required them to work from sunrise to sunset, 7 to 9 hours a day, 6 days a week. They were expected to complete a task each day before returning home. The task, however, was judged by what a stalwart creole worker could complete in the specified time. It was thus difficult for an unacclimatized worker to complete the task. Field labourers were paid $2.50 a month, which was less that the 32 cents a day paid to the ex-slaves. Besides supplying Indians with rations, the planters allowed them to cultivate small kitchen gardens.

Not long after the arrival of the “Gladstone Coolies,” Governor Henry Light (1838-1848) reported that they were “supplied well, lodged well, and though on limited wages in comparison with free labour, yet are as carefully protected from oppression, and their complaints redressed as speedily as those of other labourers.” He described Indians on Gladstone’s properties as “a fine healthy body of men – they are beginning to marry or cohabit with the Negresses, and to take pride in their dress – the few words of English they know… proved that ‘Sahib’ was good to them.” This statement about cohabitation was highly exaggerated as only one or two cases were reported.

Yes, the East Indians came as Indentured Labourers. It was on May 5, 1838, the first ship landed on British Guiana shores which continued until 1917 bringing Indentured Labourers to work in the sugar estates. John Gladstone, the father of the British statesman, applied for permission from the Secretary of State for the Colonies to recruit Indians to serve in Guyana for a five-year period of indenture. Gladstone himself owned a sugar plantation in West Demerara. Gladstone’s proposed venture was supported by a number of other sugar planters whose estates were expected to obtain some of the Indians to be recruited. By this time Indians were being taken to Mauritius to work on the sugar plantations and were proving to be very productive. Gladstone’s request was granted and he, Davidson, Barclay and Company, Andrew Colville, John and Henry Moss, all owners of sugar plantations in Guyana, made arrangements to recruit 414 Indians. Of these 150 were “hill coolies” from Chota Nagpur, and the remainder were from Burdwan and Bancoorah near to Calcutta.

Tips:

- The East Indians in Guyana are also known as Indo-Guyanese or Indian-Guyanese.

- The word “coolie”, a corruption of the Tamil word “kuli”, referred to a porter or labourer.

- May 5th has been designated as the Indian Arrival day and is celebrated annually.

The East Indians

Early Indian indentured arrivals | By SMU Central University Libraries – https://www.flickr.com/photos/smu_cul_digitalcollections/13227675614/, No restrictions, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=53440284

The indentured servants were required to sign a contract, the terms binding their service to a plantation for five years, while earning a fixed daily wage. Once this five-year period had passed, they would have another five years of industrial residence in Guiana, then they were entitled to free repatriation. At the end of the contract, labourers either returned to India or stayed in British Guiana. Those who stayed received land and money to create their own businesses.

Most of the immigrants spoke a dialect of Hindi and came from the provinces of Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, and Madras (today is known as Tamil Nadu). Within a decade, Indian immigration was largely responsible for changing the fortunes of the sugar industry, the mainstay of the economy, from the predicted ‘ruin’ to prosperity.

Did You Know? The East Indians evolved over the years to become the single largest ethnic group in Guyana and branched out of sugar into all aspects of economic and political life in Guyana.

What The East Indians Contributed To Guyana

East Indian Women & Children

The East Indians are responsible for and credited with the success of the rice and sugar industries along with the success of agriculture in general. Also, they are responsible for the success of the development of many Land Development Schemes.

Food:

- Dhal and Rice

- Roti and Curry

- Dhal Puri

- Seven Curry

- Sweetmeats e.g Mithai, Parsad, etc.

Dress:

- Sari

- Orhni

- Shalwars

- Kurtas

- Lahenga

Jewellery:

- Earrings (Some from ears to nose)

- Nose Stud

- Rings

- Heavily Ornamented Necklaces

- Bracelets

- Bangles

- Brooches

- Anklets

- Finger Rings

Musical Instruments:

- Sitars

- Mandolins

- Tassa

- Dholak

- Table

- Harmonium

- Dhantal

Dances:

- Kathack

- Nagara

Holidays/ Festivals:

Most East Indians are Hindus and Muslims and few are Christians. Some festivals observed by the Hindus and Muslims are:

- Eid-ul-Adha (Muslim Holiday)

- Eid-ul-Fitr (Muslim Holiday)

- Youman Nabi (Muslim Holiday)

- Phagwah (Hindu Holiday)

- Diwali/ Deepavali (Hindu Holiday)

Land Development Schemes

Some Land Development Schemes were instituted to encourage the East Indians to stay in Guyana. Some of these Land Development Schemes were in the following areas:

The East Coast, Demerara

- Cane Grove

- La Bonne Mere

- Strathaven

- Helena

- Nooten Zuill

Berbice

- Bush Lot (West Coast)

- Whim (Corentyne)

- Black Bush Polder (Corentyne)

Essequibo

- Huis’t Dieren

- Anna Regina

- Vergenoegen

On these Schemes, the major crop grown was rice; the immigrants also farmed the land with green vegetables and ground provision. East Indians still live in those areas mentioned above.

East Indians In Guyana (Indo-Guyanese)

At the 180th Anniversary of Indian Arrival, President David Granger applauded the contributions of Indian indentured immigrants and their descendants to the building of Guyana, as he noted that the country is now richer, culturally and socially because of these contributions. He went on to say, “They turned their indentureship into citizenship. From an economic point of view, Indians helped to transform the country that they adopted, what was then British Guiana. Indian skills in paddy and vegetable-farming, coconut-cultivation and cattle-rearing; and their skills as boatmen, charcoal-burners, goldsmiths, fishermen, hucksters, milk and sweetmeat vendors, shopkeepers and tailors enriched the entire economy. These are skills they brought from their homelands. All of these skills enriched the Guyanese society. We are richer now with Indian immigration. They brought their customs from the Indian villages and created villages in Guyana based on those customs and culture. Indian resourcefulness and their agrarian roots in rural India were transplanted in Guyana.”

See also Whitby – The Way East Indian Came To British Guiana.

Article References:

- https://exploreguyana.org/event/indian-arrival-day/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indo-Guyanese

- https://www.thewestindianonline.com/guyana-is-richer-because-of-indian-immigration/

- http://www.guyana.org/features/guyanastory/chapter50.html

- Main Image: Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=372956

Discover more from Things Guyana

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.